Storm over the Pacific

Typhoon Cobra and the day the U.S. Third Fleet fought for its life

In Japan, legend has it that in August 1281, 4,200 junks carrying more than 140,000 Mongol warriors, under the command of the fearsome Kublai Khan, sailed from China and the Korean Peninsula to invade the Land of the Rising Sun. That immense army landed in Imari Bay and began to fight a thin line of samurai—the last rampart against foreign invasion. As the battle raged, a storm rose so suddenly that many junks smashed themselves against the rugged coast—and the samurai finally drove back into the sea invaders a hundred times more numerous than themselves. The emperor saw in this reversal the hand of the gods who, by their “divine wind” (kamikaze), had saved Japan.

With that story in mind, in October 1944 the Imperial Japanese Navy, on the edge of the abyss, launched its very first “special attack”—the other name for the suicide operations carried out by certain fighter-bomber squadrons. The first results of these one-way raids seemed to justify the sacrifice of successive intakes of veterans and then trainee pilots, and from November the Imperial Army created its own volunteer squadrons as well, throwing them straight into the furnace. At that point, the hottest sector of the Pacific War was the Philippines. MacArthur landed on Leyte with 200,000 men on 20 October, and Nimitz soundly defeated three Japanese fleets in the gulf of the same name on 23 and 27 October. It was therefore across this vast theatre that the kamikazes concentrated their attacks, destroying—in eight weeks—one escort carrier, three destroyers, two LSTs, and several transport ships. Many other vessels, however, endured the fanatical assaults of these “special units” and were damaged to varying degrees. The appearance of kamikazes changed nothing in the strategic situation nor in the balance of forces, which remained strongly favourable to the U.S. Navy—but it did blow a “wind of panic” through even the most battle-worn American crews. The constant alarms, and enemy pilots with no fear of dying, had a real psychological effect on sailors already exhausted by the usual stresses of combat. And far from being confined to a few areas, the kamikaze phenomenon seemed to be spreading, even as the securing of the Philippines had barely begun: Leyte was now safe, but to seize Luzon, the Americans first had to secure Mindoro and its airfields. The operation was launched on 12 December 1944 (Operation “Love III”) with the landing of two regiments, brought to the beaches by Admiral Kinkaid’s fleet. The kamikazes took their toll by crashing into several ships, but that did not prevent the amphibious operation from being a major success.

Destination Tokyo

In preparation for “Love III”, Task Force 38 (Vice Admiral McCain1) sailed from Ulithi on 11 December with orders to contribute to the air cover of the landing—more specifically, by conducting a continuous series of strikes against Japanese airfields on Luzon. The force comprised three heavily armed task groups, bringing together 13 aircraft carriers (6 fleet carriers and 7 light carriers), 8 battleships, 13 cruisers, and 56 destroyers.

Task Force 38 on 11 December 1944

TG 38.1 (Rear Admiral Montgomery)

• Aircraft carriers: USS Yorktown, USS Wasp, USS Cowpens, USS Monterey

• Battleships: USS Massachusetts, USS Alabama

• Cruisers: USS San Francisco, USS Baltimore, USS New Orleans, USS San Diego

• Destroyers: 18 units

TG 38.2 (Rear Admiral Bogan)

• Aircraft carriers: USS Lexington, USS Hancock, USS Hornet, USS Independence, USS Cabot

• Battleships: USS New Jersey, USS Iowa, USS Wisconsin

• Cruisers: USS Pasadena, USS Astoria, USS Vincennes, USS Miami, USS San Juan

• Destroyers: 20 units

TG 38.3 (Rear Admiral Sherman)

• Aircraft carriers: USS Essex, USS Ticonderoga, USS Langley, USS San Jacinto

• Battleships: USS North Carolina, USS Washington, USS South Dakota

• Cruisers: USS Mobile, USS Biloxi, USS Santa Fe, USS Oakland

• Destroyers: 18 units

On 13 December, the carriers refuelled from the force’s oilers and then launched their air groups. The raids lasted three consecutive days and the tempo was intense: in 1,427 fighter sorties and 244 bomber sorties, the Americans destroyed 170 Japanese aircraft, four merchant ships, three landing barges2, and damaged one corvette, at the cost of 27 aircraft lost in combat and 38 more lost to accidents. Mechanical failures and weather—sometimes in combination—thus caused more losses than Japanese AA fire and aviation. On the 16th, the ground operations were complete, and the next day TF 38 sailed as a whole to refuel 500 nautical miles east of the Philippines, from its auxiliary ships.

Those auxiliaries were so numerous that the U.S. Navy grouped them into an ad hoc formation, TG 30.8, which included 12 oilers, seven transports (ammunition, food, material, etc.), five escort carriers (tasked with flying CAP3, but also with supplying spare aircraft parts and replacement pilots to TF 38), seven ocean-going tugs, and—just to be safe—a protective screen of roughly forty escorts. This logistics armada carried 100,000 barrels of fuel oil and three million litres of aviation gasoline, and it was commanded by Captain J. T. Acuff, a former submariner who split his force into three sub-groups so as to refuel McCain’s three task groups simultaneously at rendezvous points fixed in advance.

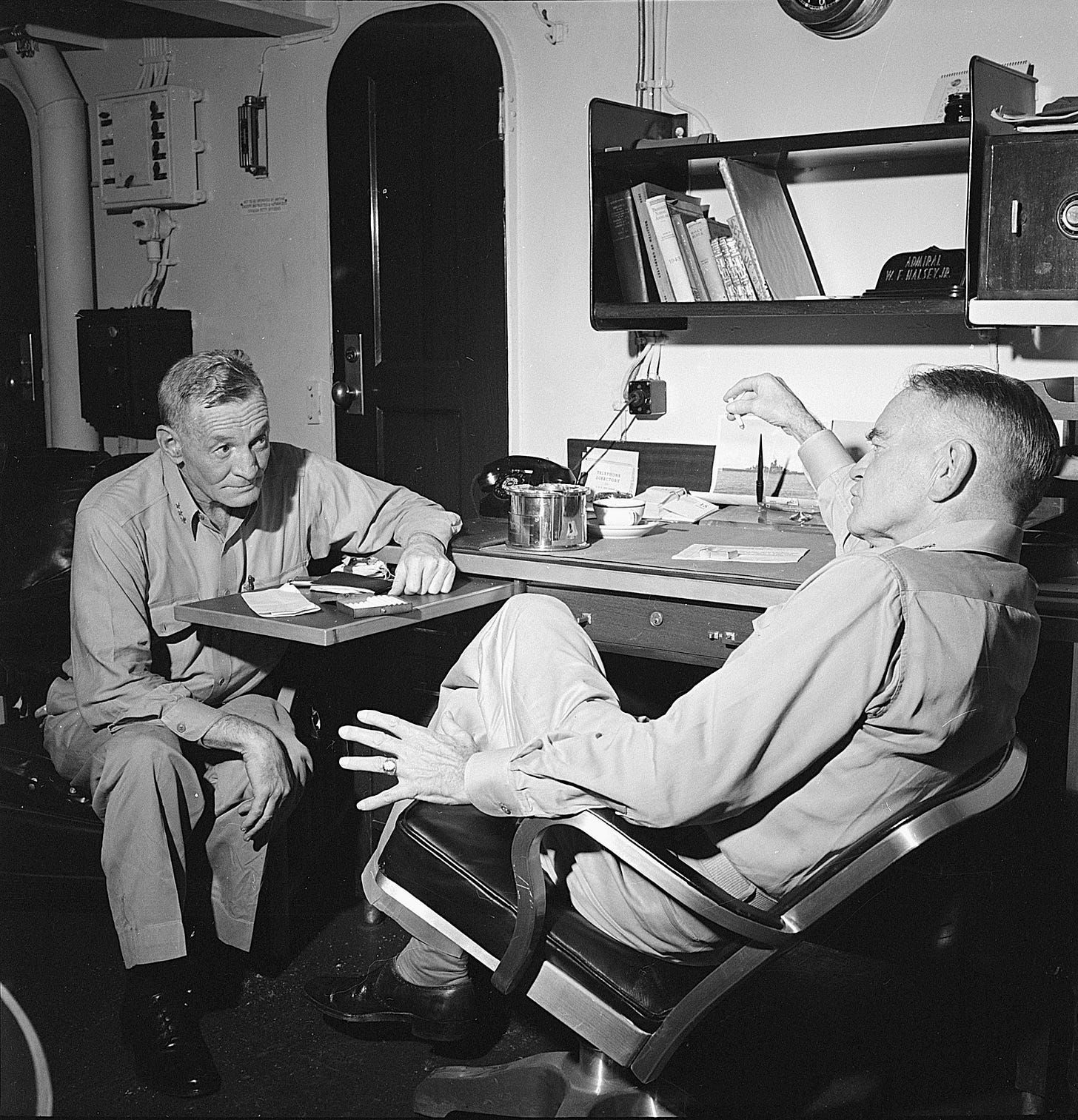

If there is one factor that matters when refuelling at sea, it is the weather. Thanks to long flexible hoses, a modern oiler can refuel two ships at once, one on each beam (and sometimes even a third astern), provided all ships maintain the same speed and course and keep only a few metres between them. That was still technically impossible early in the war, but the British and the Americans made enormous progress. The method, however, requires calm seas and light winds to avoid increasing the risk of collision. Acuff’s main task was therefore to determine where and when—given McCain’s operational constraints—refueling would have the best chance of proceeding smoothly: out of enemy reach and under benign weather. On that last point he worked closely with Commander George F. Kosco, McCain’s chief meteorologist since October 1944. In the 1930s, Kosco had studied hurricane formation in the Caribbean at length, becoming one of the leading American specialists in tropical phenomena. Aboard the battleship USS New Jersey, he led a seven-man team responsible for forecasting weather for the entire 3rd Pacific Fleet (of which TF 38 was the main component).

Kosco knew better than anyone that modern meteorology was still unable to define typhoon movements and intensity with real precision. Only in 1944 did the U.S. Navy begin to systematize weather reconnaissance flights to detect tropical disturbances that might become typhoons—yet there were not enough aircraft to cover all sectors effectively. And while every major unit carried a weather station, its instruments (barometer, thermometer, anemometer) were not very different from what sailing ships had already carried in the 18th century. In short, weather was not a Navy priority, and the reporting chain was riddled with gaps. Thus, on 11 December, the Pearl Harbor Fleet Weather Station did detect what might have been the formation of a tropical storm in the Northwest Pacific—but it triggered no warning.

The Wind Rises

A tropical cyclone is the final stage of a meteorological phenomenon specific to certain parts of the world, which typically passes through four successive phases: wave, disturbance, depression, and storm. This evolution is defined by the average wind speed and by the rise in sea level (the storm surge) that it causes along coastlines—usually a sharp, rapid local increase. Depending on the region, the same phenomenon is named differently: “hurricane” in the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, “cyclone” in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific, and “typhoon” in the Northwest Pacific; but it is also called “baguios” in Manila, “tufans” in Muscat, “taai fungs” in Hong Kong, and so on. In the West, since the 18th century, each tropical cyclone has been given a name to distinguish it from others, and several naming systems have followed one another over the last decades. Thus, until the Second World War, U.S. forces used their radio phonetic alphabet paired with the year. During the conflict, the U.S. Navy weather service sometimes assigned a nickname (“Cobra” in 1944) or a woman’s first name (“Helen” in 1945, for example) to identified typhoons.

On average, 15 typhoons and 25 tropical storms per year cross the part of the Pacific stretching between the Philippines, Japan, and China, sometimes continuing as far as the Aleutians. Given the immensity of the waters involved, these extreme events can last for weeks and extend over thousands of kilometres. It is no coincidence that, since the 18th century, American sailors have nicknamed the North Pacific “Typhoon Alley.” The “cyclone season” usually runs from July to October in the Northwest Pacific, but that is far from an iron rule: nearly a third of typhoons form outside that window, which complicates surveillance. Another key feature: late-season typhoons are particularly unpredictable. They normally track northwest, but in some cases can abruptly change direction without warning.

The Saffir–Simpson scale

Since 1969, the Saffir–Simpson scale has been used to describe the potential effects of tropical cyclones on human infrastructure by classifying their intensity into five levels. It is officially used only for hurricanes (tropical cyclones of the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific), but equivalencies exist with other typhoon measurement systems—hence its use in this article. On land, Category 1 cyclones have sustained winds from 119 to 153 km/h, with a storm surge of 1.2 to 1.5 m, enough to inflict significant damage on port facilities and roofs. Category 2 cyclones (154 to 178 km/h and 1.8 to 2.4 m) are powerful enough to uproot trees, severely damage urban infrastructure, and cause casualties. By comparison, Hurricane Katrina (280 km/h), which devastated New Orleans in 2005, and Hurricane Irma (297 km/h) in the Antilles in September 2017, are classified as Category 5, even though some specialists have suggested creating a Category 6 to accommodate such storms.

On 15 December, still aboard USS New Jersey, Kosco was informed by the Saipan weather station that a tropical storm had been spotted less than 200 nautical miles from Ulithi, TF 38’s main logistics base. The data suggested it was about 800 nautical miles southeast of McCain’s three task groups and tracking northwest. Like Admiral Halsey, Kosco was not especially worried: this was not the first time the 3rd Fleet had encountered a typhoon. In September, the fleet had already crossed a major one without serious trouble; and in early October, Halsey had even used another to leave Ulithi undetected, approach Okinawa, and launch air raids on the Japanese-held islands. That typhoon had been so useful that the Americans jokingly nicknamed it “Task Force 0-0.” On 16 December, Kosco repositioned the disturbance about 500 nautical miles east of TF 38 and informed Halsey at once, while adding that “it is not necessarily a typhoon”. He was all the more relaxed because he knew a Siberian cold front—a “cyclone killer”—was descending and should swallow the system long before it reached the fleet.

What Kosco did not know—and could not predict—was that during the night of 16–17 December, the storm transformed into a cyclone with a 6-nautical-mile-wide eye, winds above 64 knots, and a steady movement of 9 knots toward the north-northwest. In retrospect, the Americans would nickname it “Cobra,” the name we will use from this point on.

Kosco’s calm forecasts therefore did not call Halsey’s plans into question. Halsey had received orders from Nimitz to return and cover MacArthur’s forces off Mindoro once his fleet had refuelled from Acuff’s auxiliaries. The need was acute, especially for the destroyers: to stay close to the battleships and carriers they screened, they ran most of the time at high speed, and after three days of that pace their fuel bunkers were nearly empty. Halsey therefore ordered TF 38 to leave its patrol area for the planned rendezvous points 400 nautical miles farther east, with refuelling to begin the next day at 08:00.

“Here’s the story of the Hurricane”

On 17 December at 05:00, a seaplane out of Ulithi sighted Cobra 225 nautical miles southeast of the 3rd Fleet’s three rendezvous points—about 250 nautical miles closer than Kosco had estimated the day before. The information was important, and the pilot wrote a report to that effect as soon as he returned to base. But because the message had to be manually encoded and then passed through a complex administrative circuit, Halsey would not receive it until nine hours later, buried in a pile of communiqués of mixed importance. Because of that breakdown, Kosco himself would not read the report until 36 hours later.

Nor was that the only malfunction. The Guam and Saipan weather stations also tracked the approaching system through observations and reconnaissance flights. They informed the Fleet Weather Central at Pearl Harbor, stating it was probably a typhoon and appeared to be heading north—straight toward the 3rd Fleet’s operating area. Pearl Harbor’s reply was so unbelievable it speaks for itself: “We do not believe you.” Saipan insisted, stating its report was not guesswork, but Pearl Harbor held its position: “We still do not believe you, but we will look.”

Meanwhile Cobra strengthened considerably, with sustained winds around 80 knots and gusts up to 120 knots. It remained compact enough that TF 38 did not perceive anything truly alarming, even though the sea state worsened. In his log that morning, Halsey noted: “Force 5 wind—fresh breeze.” On the light carriers, however, the swell became problematic and their commanding officers repeatedly asked that their CAP aircraft land preferably on the larger, more stable fleet carriers to avoid crashes. A few hours later the winds were so strong that Halsey forbade all takeoffs. Aircraft were then tightly lashed down and their tyres deflated. The men expected to pass through the weather without major difficulty, as they had already done several times. Conditions and forecasts were far from alarmist and did not change TF 38’s priorities: refuel, then return to combat.

Aboard the destroyers, the storm made life miserable. Lightly ballasted because their fuel tanks were nearly empty, the ships rolled dangerously from side to side. They were soon ordered to flood ballast tanks with seawater to reduce roll—which only drove the battered units deeper into the waves.

During the night of 16–17, the start of refuelling was moved up to 07:00 to avoid the worst of the storm, but it was not enough. The sky was completely overcast, winds intensified again, and a cross-sea developed. At the appointed hour, the destroyers were almost incapable of positioning themselves correctly alongside the oilers, to the point that parallel replenishment was cancelled. The oilers that could do so attempted astern (“in-line”) replenishment to reduce collision risk, but that too proved impossible: the seas and winds were simply too heavy.

Halsey was now trapped: his destroyers would run dry before refuelling—in the middle of a storm, something unprecedented in the U.S. Navy. Farragut- and Fletcher-class destroyers were especially hard-hit: top-heavy because of added radar aerials and AA weapons, and down to only 10–15% of their fuel reserves, they were tossed about like straws. Shortly after noon, USS Spence had no choice but to come alongside USS New Jersey on the battleship’s starboard side to pump fuel from her tanks. The manoeuvre was judged less dangerous than using an oiler because the battleship’s imposing freeboard was supposed to shield the destroyer from gusts and seas. In reality, the Spence struggled to stay level; her mast even struck New Jersey’s rail—fortunately without further consequences. At the same time, the destroyer USS Collet failed to pass its lines to USS Wisconsin, while the Maddox narrowly avoided the oiler Manatee, beside which it was vainly trying to refuel. The cruiser USS San Francisco even had to threaten to cut the hoses a destroyer (USS Brown) had just passed over, in order to force the Brown to abandon a manoeuvre deemed too dangerous.

Halsey suspended refuelling and, on Kosco’s advice, set new rendezvous points 160 nautical miles northwest for the morning of the 18th—a course that ran parallel to Cobra’s projected track. Only at 15:00 did Kosco finally receive a reliable report from Pearl Harbor stating the typhoon had also changed course. He informed Halsey immediately, and at 15:30 Halsey transmitted new rendezvous coordinates 185 nautical miles due south.

Gone with the Wind

The destroyers Spence, Maddox, and Hickox had so little fuel left that Halsey removed them from TF 38’s screen and authorized them to refuel at the first opportunity from Acuff’s oilers. That was how the Spence collided—for the second time in 24 hours—with a ship meant to refuel her. This time there were injuries, and any further parallel replenishment was formally forbidden. Passing a flexible hose astern for in-line replenishment proved just as impossible, despite repeated attempts to pass a towing line on floats. Winds were rising still further: USS Dewey, for example, took a 20° list with each gust. Several ships also warned Halsey that under present conditions they would never reach the rendezvous in time. Shortly before midnight, the admiral issued yet another one—the third in 12 hours—halfway between the first two.

With winds now exceeding 100 knots, the worst was that Kosco had still not pinned down the cyclone’s exact eye position or direction. Only around 03:00 did he understand he was not dealing with a mere storm but with a massive typhoon. That changed everything: in a cyclone, it is recommended that all ships abandon formation and face wind and seas as best they can. It was a wise but serious decision, because it meant the fleet would not be operational for some time—long enough to regroup after the typhoon passed. At 05:00, Halsey cancelled the rendezvous and ordered his task groups to refuel “as soon as possible” after daybreak. Among ship captains the reaction was disbelief: how did their admiral think they could even steam that long? Many had already been fighting for hours against 100-knot gusts.

One of the first victims was USS Aylwin, the Farragut-class destroyer on which Acuff had hoisted his flag. After a wave threw her to a 70° port roll around 03:30, water flooded aboard and drowned the generators, cutting power, lighting, and steering control systems. Within minutes the ship was out of control, and at 03:48 her captain transmitted: “Aylwin to TG 30.8. Dead in the water. Have lost all generator power. Trying to return to base course.” USS Monaghan was so badly battered she could not change course. Her commanding officer, Captain Garrett, a novice in post for only a week, decided to flood ballast tanks with seawater to improve stability—a suicidal choice. Heavier, the destroyer shipped more and more water; her generators soon failed, then her steering. Garrett barely had time to send a distress call before communications failed as well.

At 06:16, Vice Admiral McCain suddenly ordered a 120° course change, from due south to a northeast axis. Halsey knew that amounted to steering straight into the typhoon, but he let it happen, perhaps hoping they could still punch through without major damage. It was a catastrophic misjudgment: most units were already at the end of their tether, literally fighting for survival. The tug Jicarilla requested assistance because of mechanical problems; the carrier USS Independence had two men swept overboard; USS Hickox became uncontrollable after flooding in the engine room; and so on.

On USS Hull (Farragut class), half-flooded, panic turned into near-mutiny when the crew learned—listening to radio traffic—that they faced a typhoon, not a storm4. Aboard the large, steady USS New Jersey, Halsey could not grasp what his smallest units were enduring. Still, after 08:00, he had to acknowledge that refuelling was impossible and informed MacArthur that the fleet would not return off Luzon as planned on the morning of the 19th, but rather on the 21st. That estimate alone shows how far he still was from recognizing the severity of the situation. Consequently, even though Kosco had revised his view, Halsey still refused to open distance from the typhoon so that he could return to the Philippines as quickly as possible once conditions allowed. In a message to Nimitz around 09:15, he even referred to a “tropical disturbance,” not a cyclone.

And yet damage and loss reports kept piling up. The destroyer USS Grayson had her bow deformed by a wave and her aft gun carried away by another. The light carrier USS Monterey, already suffering steering and boiler problems and a 25° port list, now saw her hangar go up in flames: her 35 fighters and torpedo-bombers broke their lashings and smashed into each other, sparking serious fires. Halsey offered Monterey’s commanding officer, Captain Ingersoll, permission to abandon ship; he refused. He reorganized firefighting parties and at 09:41 transmitted: “Fire under control. Prefer to drift until we can [again] make the task group’s speed.” The tally in the devastated hangar was quickly made: 18 aircraft destroyed, 16 seriously damaged.

Aboard USS Cowpens, fires also raged; the carrier was saved only because gusts tore away metal shutters from the hangar side openings, allowing seawater to pour in and flood everything. The Cowpens needed the help of the cruiser USS Baltimore and three destroyers to regain station. On escort carrier USS Altamaha, a fire was extinguished by onboard systems, but two-thirds of the aircraft had to be jettisoned overboard. USS San Jacinto faced the same danger and was saved only by the courage of her crew. Aboard USS Cape Esperance, aircraft slammed from side to side across the flight deck with each wave, smashing most of the AA mounts below; all aircraft but one would go overboard before the typhoon ended. USS Langley fared better, though she still rolled up to 70°, while the captain of USS Kwajalein soon reported losing control of his escort carrier.

Battleships and cruisers proved more resilient and suffered only light damage, generally the loss of their Kingfisher seaplanes, exposed on their catapults (on USS Wisconsin and Boston, for example). Inside the ships, however, furniture and objects literally flew despite all efforts to lash them down.

The Great Wave

Some ships recorded winds of 125 knots, enormous seas, and zero visibility, with sheets of water smashing against bridges almost vertically. At 11:49, Admiral Halsey finally ordered by radio that the fleet abandon formation, but he still took two more hours to issue a typhoon warning to Fleet Weather Central. Destroyer crews in the 3rd Fleet might have laughed at such late messages. Aboard USS Taussig, Dr. Blankenship had to be strapped to the operating table to perform an emergency appendectomy. USS Dewey, unaware she was steaming through Cobra’s heart, soon had her forward stack torn away by wave pressure—taking with it at least two ammunition lockers and the whaleboat. On USS Aylwin, two men went overboard and the captain had to stop engines and drift under the combined hammer blows of wind and sea. With no power and electrical short-circuit fires breaking out, the ship was out of control.

The same was true of USS Monaghan, where the only instrument still working properly was the inclinometer—showing rolls exceeding 78°. The destroyer would not last long. Laid over on her starboard side repeatedly by the wind’s violence, she soon disappeared beneath the surface, weighed down by all the water she had shipped. Only six of her roughly hundred-man crew escaped the suction of the sinking hull. Clinging to a life raft, they would wait three days before rescue.

Stopped head-to-wind, USS Hull was prey to gigantic waves that had already carried away a whaleboat and her depth charges. She rolled beyond 80° and kept taking on water. Around noon she finally lay over on her side. When water surged into pressurized boilers, the reaction was explosive, killing many men; the ship then sank rapidly. USS Spence, for her part, eventually capsized under the seas. As men still trapped in the inverted wreck tried to escape, the destroyer almost broke in two and went down, taking 317 crewmen with her—under the horrified eyes of 23 survivors clinging to whatever debris still floated.

Not far away, USS Tabberer was also fighting for her life. This destroyer escort did not belong to McCain’s force at all but to TG 30.7, responsible at that time for ASW defense east of the Philippines. She was patrolling when the typhoon hit with rare violence. On the evening of the 18th, a gust carried away her mast and radio aerials; while attempting repairs, a crewman spotted a man overboard. Despite the conditions, the castaway was recovered alive around 21:30—a sailor from USS Hull. The Tabberer was thus the first ship to learn of the unfolding tragedy, but could not communicate it. Her captain decided to steam toward the disaster area to search for additional survivors. On the 18th, the lack of radio contact from the Spence, Hull, and Monaghan began to worry Halsey’s staff. Shortly after 02:00 on the 19th, the disaster was confirmed by a message from USS Dewey, which had happened to run into the Tabberer and communicate by flashing light. Halsey immediately ordered the Tabberer to return to Ulithi—an order her captain promptly disobeyed. Instead, he continued searching until the 20th, picking up 55 more survivors from the Hull and Spence5.

The Perfect Storm

On the 19th, Cobra weakened, allowing the larger ships of TF 38 to refuel at last from Acuff’s oilers at the planned rendezvous. Halsey then sent rescue forces into the area where the Hull had gone down. In total, 93 sailors from the three lost destroyers were recovered. For the 3rd Fleet the consequences were devastating: in a few days it lost three ships, 790 men, and at least 146 aircraft. In addition, 80 sailors were injured and nine ships were so badly damaged that they required urgent repairs.

For Halsey, Cobra would remain an indelible stain on his record. The affair naturally made international headlines, and the U.S. Navy had to open an investigation, which produced a 200-page report on 3 January 1945. The report cited the instability of Farragut-class units and the inexperience of their commanding officers as the main causes of the loss of the Hull and Monaghan, while exonerating the captains of damaged ships. It confirmed the responsibility of chief meteorologist Kosco, as well as Vice Admiral McCain and Admiral Halsey, guilty of “errors of judgment.” Nimitz nonetheless preferred to take no disciplinary action against them, even though he acknowledged in his correspondence that this disaster “was the greatest loss we suffered without compensation in the Pacific since the First Battle of Savo Island.” Even so, Halsey would have to hand over the 3rd Fleet to Spruance until May 1945.

A few days after taking command again, Halsey committed another “error of judgment” by running into yet another typhoon. Barely less violent than Cobra, Connie caused the loss of six sailors and the destruction of 75 embarked aircraft—again without career consequences thanks to Nimitz’s protection. Operationally, however, the U.S. Navy worked to avoid repeating its forecasting and communication failures. In June, a Fleet Weather Center/Typhoon Tracking Center was created on Guam, and technical studies were launched to integrate the typhoon problem into the design of future warships.

Major typhoons of 1944–45 (Northwest Pacific)

14–19 December 1944: Cobra (Philippine Sea), 160 km/h - Category 2

1–7 June 1945: Connie (Philippine Sea and East China Sea), 130 km/h - Category 1

7–15 September 1945: Ursula (Philippine Sea and East China Sea), 165 km/h - Category 2

2–12 October 1945: Louise (Philippine Sea and East China Sea), 150 km/h - Category 1

John S. McCain Sr. was the father of Admiral John Sidney McCain Jr. (Commander, U.S. forces in Vietnam, 1968–1972) and the grandfather of Senator John S. McCain III (naval aviator, POW in North Vietnam, 1967–1973).

Including the Oryoku Maru, which carried 1,600 Allied prisoners…

CAP: Combat Air Patrol—patrols intended to protect a carrier task force from enemy air raids.

This episode inspired novelist Herman Wouk, who wrote The Caine Mutiny (Pulitzer Prize, 1952), later adapted for film with Humphrey Bogart (1954).

For this, Halsey personally awarded Captain Henry Lee Plage the Legion of Merit, and his crew the Navy Unit Commendation Ribbon.

Fantastic write up!

Thank you for this account. My father was in the Navy during WW2.

This tragic story has not been sufficiently memorialized.